Well in reality it would be scientific revolution, and a cultural one. Not only would we have amazingly quick and easy access to Mars and other nearby planets, this ship would be, in essence, a moving space station. Something of this magnitude could park in Earth orbit for a month, trading data and resources, then take off to Mars, maybe stopping at the Moon along the way. It would also make launching probes a lot easier. Probes could be accelerated with the ship and released during turnaround (when a ship is at max velocity, about halfway through the trip, it turns around and burns in the opposite direction to bring it to a relative velocity of zero) toward its intended target; much cheaper since its incorporated into an existing system.

More science fiction right? Well no, not really. We have everything we need to build this type of ship right now. Now granted, it would cripple the United States economy to the point of turning us into a third world country, but who says this is a job for just us? If this became a UN project, it could be done feasibly without killing anyone's economy.

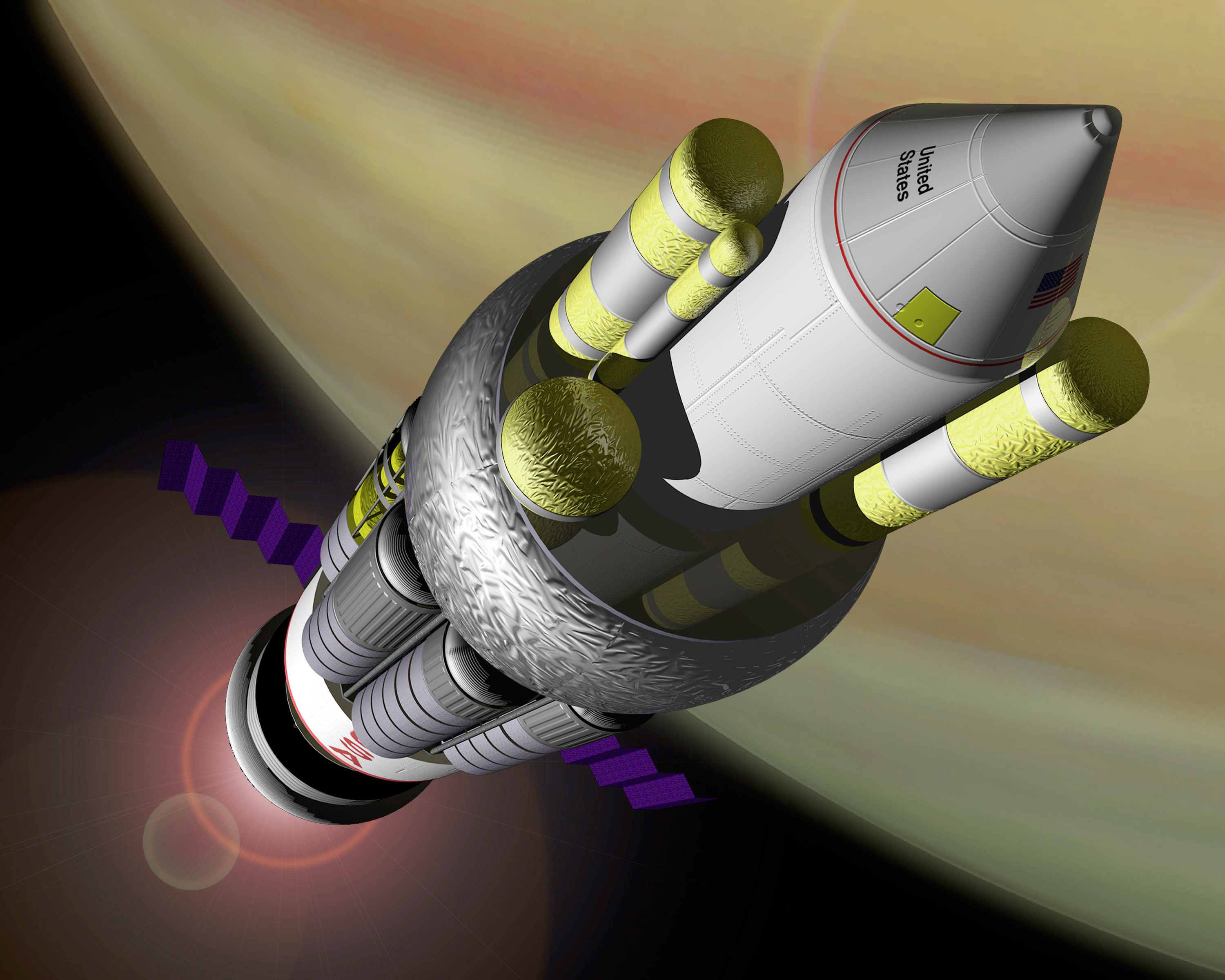

Something of this size needs a pretty big engine. There are all sorts of possibilities, an ion engine, a small nuclear pulse engine, or even slave the old engines from the Shuttles, for a taste of nostalgia. Any way you spin it, those engines will need power, and a lot of it. Obviously we can't use petrol, we shouldn't be using it here on Earth at all, using it in space would be equally or more idiotic. You could use a fission generator, but even those would be dirty and a big problem to keep safe for the people riding along. Imagine flying through space in an airtight can with a nuclear bomb behind your seat. Not a pleasant thought right? So what does that leave us? Tokamak. Magnetically accelerated plasma spun around a toroid until fusion is achieved. It might not sound like it, but it's actually a lot safer than a typical fission reactor, and a lot more powerful.

So now that she's got some engines, we can worry about the people. How do you house that many people "comfortably" in a ship. Well there are quite a few solutions. While the ship is moving at a constant velocity (when you're in your car moving down the highway, you don't experience any forces, you only feel that pull when you're speeding up or slowing down) all you have to do is spin it. Whether you spin the whole ship or just a small ring for habitation, its absolutely necessary to keep those people used to gravity. People can survive in zero gravity indefinitely if needed, but if they did that, they'd never touch ground again. A child born in zero-gee would be killed by the gravity on the surface of Earth.

So now that she's got some engines, we can worry about the people. How do you house that many people "comfortably" in a ship. Well there are quite a few solutions. While the ship is moving at a constant velocity (when you're in your car moving down the highway, you don't experience any forces, you only feel that pull when you're speeding up or slowing down) all you have to do is spin it. Whether you spin the whole ship or just a small ring for habitation, its absolutely necessary to keep those people used to gravity. People can survive in zero gravity indefinitely if needed, but if they did that, they'd never touch ground again. A child born in zero-gee would be killed by the gravity on the surface of Earth.It seems like a frivolous idea, and in some ways it just might be. But all I've ever needed to convince myself was the idea of seeing this ship built in orbit. Imagining the live video feeds as this ship forms, watching with the world when she fires up her engines, holding my breath when the Tokamak is lit. Something like that would change us as a people.