...Power a Warp Drive! I'll be calling it an Alcubierre Drive, because Miguel Alcubierre was the man who worked out the physics, and he deserves more credit then he gets, but the idea would be completely familiar to any Trekkie out there. You take the space infront of you and crunch it down, while you expand the space behind you. The result is faster than light (superluminal, FTL) travel with absolutely no funky dilation. Typically when you talk about FTL and don't use a word like "hyperspace", you have a bit of a problem. If you could accelerate past the speed of light, ignoring energy limitations, time would literally flow backwards onboard your ship. Paradoxes galore!

...Power a Warp Drive! I'll be calling it an Alcubierre Drive, because Miguel Alcubierre was the man who worked out the physics, and he deserves more credit then he gets, but the idea would be completely familiar to any Trekkie out there. You take the space infront of you and crunch it down, while you expand the space behind you. The result is faster than light (superluminal, FTL) travel with absolutely no funky dilation. Typically when you talk about FTL and don't use a word like "hyperspace", you have a bit of a problem. If you could accelerate past the speed of light, ignoring energy limitations, time would literally flow backwards onboard your ship. Paradoxes galore!But thanks to Alcubierre, we might have a solution. The Alcubierre drive isolates the ship in a bubble of normal space time, so time would pass exactly the same inside as outside the "Warp Bubble". If you look at the picture first picture you can see a rough graphical representation of this. The flat grid is normal spacetime, while the z-axis represents a positive or negative shift in the "stretch" of space. On either side of the Bubble, everything is nice and flat, while the bubble itself compresses space (a negative movement in the z-axis) in front and expands behind it (a positive movement).

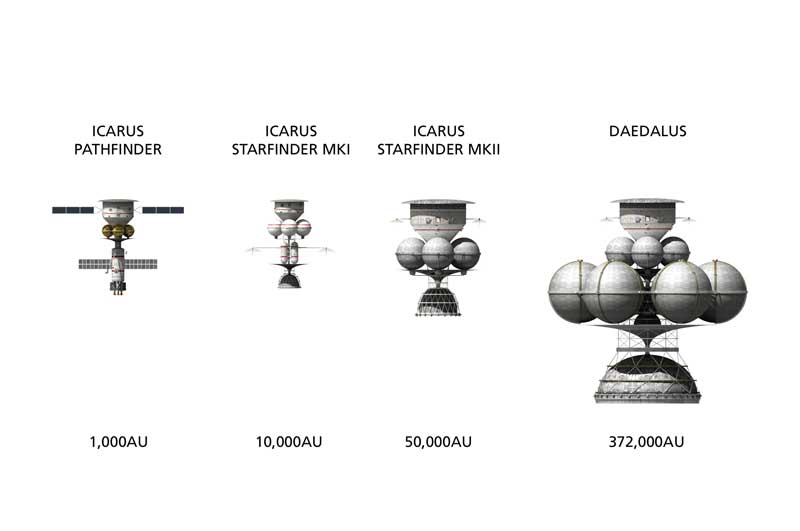

You made it this far? Awesome! So back to that metric tonne of antimatter. Recent data collected by NASA's Advanced Propulsion department (often called "the Eagleworks", after Lockheed-Martin's Skunkworks advanced aircraft testing facility) has shed new light on Alcubierre's original mathematics. Originally it was estimated that a ship of the design Miguel had in mind would require a ball of antimatter the mass of Jupiter, not very feasible right? But the Eagleworks has found that by altering the math and design of the ship a bit, you can reduce the power requirements to about a metric tonne of antimatter.

You made it this far? Awesome! So back to that metric tonne of antimatter. Recent data collected by NASA's Advanced Propulsion department (often called "the Eagleworks", after Lockheed-Martin's Skunkworks advanced aircraft testing facility) has shed new light on Alcubierre's original mathematics. Originally it was estimated that a ship of the design Miguel had in mind would require a ball of antimatter the mass of Jupiter, not very feasible right? But the Eagleworks has found that by altering the math and design of the ship a bit, you can reduce the power requirements to about a metric tonne of antimatter.Now I'll admit, that's a lot of antimatter to produce, and considering its extremely expensive and extremely dangerous, it might not seem like the best idea. So why even bother thinking about it? Well, as my grandfather once told me; "some things a man should do simply for the sake of being able to say he did them".